The music of Francesco Barsanti is an inspiring combination of art music and folk music and the man himself had a fascinating life. Unfortunately there is not much known about Barsanti’s background. His father may have been the opera librettist Giovanni Nicolao Barsanti who wrote “Il Temistocle”, but sadly this has never been proved. Like many composers, Francesco Barsanti studied law as a young man but abandoned it to pursue a career in music.

The music of Francesco Barsanti is an inspiring combination of art music and folk music and the man himself had a fascinating life. Unfortunately there is not much known about Barsanti’s background. His father may have been the opera librettist Giovanni Nicolao Barsanti who wrote “Il Temistocle”, but sadly this has never been proved. Like many composers, Francesco Barsanti studied law as a young man but abandoned it to pursue a career in music.

In 1714, Barsanti made the bold step of emigrating to London with his older colleague from Lucca, Francesco Geminiani. Playing oboe and recorder, he soon bagged a job in the prestigious Haymarket opera orchestra, performing Handel operas. There are reports that he then returned to Lucca in 1717 and 1718 to play in the festival of the Holy Cross for reportedly a rather high salary!

Having made his mark in London, Barsanti moved again in 1735 to Edinburgh where he became a ‘Master’ with the Edinburgh Musical Society. Scotland was Barsanti’s home for eight years and he married a lady called Jean there, about whom sadly no further information is known. He may have had support from Lady Erskine(Charlotte Hope) (1720-1788) as he dedicated his famous collection of Old Scots Songs to her in 1742. Unfortunately the Edinburgh Society was not well off financially and in 1740 Barsanti’s salary was halved to £25 with his repeated requests for a pay rise refused.

It seems that some time after 1743 Barsanti was forced to return to London with his wife and his daughter, named Jane (Je

nny). Unfortunately London musical society had moved on to different fashions and Barsanti was less popular than previously. Barsanti went back to play

ing in Handel’s opera orchestras and sadly was unable to eke out any income from his earlier compositions nor for the two works he composed after his return.

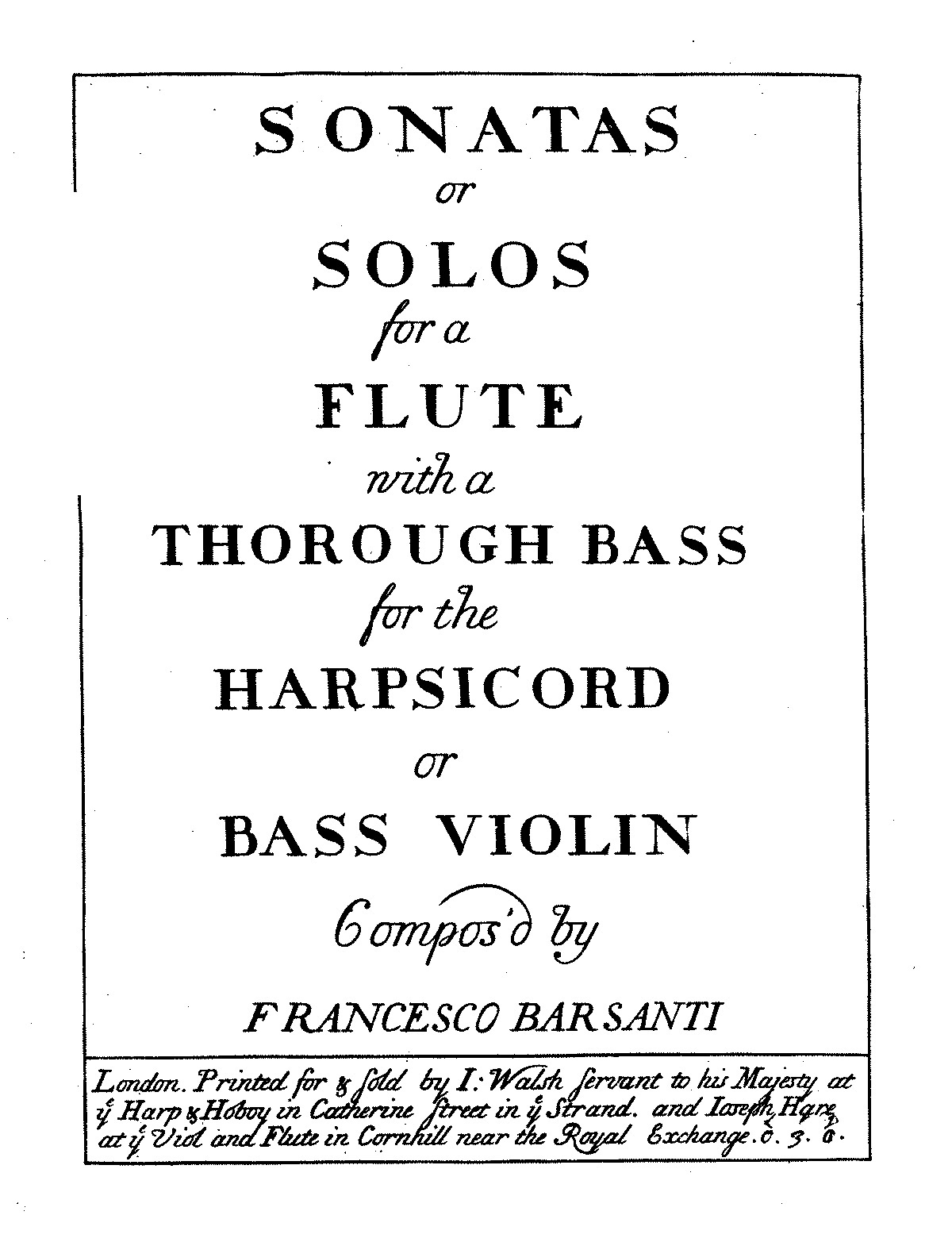

The six recorder Sonatas (Opus 1, 1724) are among the most famous of Barsanti’s works and the G minor one which we have pla

ying recently is particularly evocative with its folk style Gavotte with Variations. Barsanti had a real feel for the tone colour and capabilities of the recorder and there are fascinating effects such as double stopping in the bass part. Unbelievably the Sonatas were not performed in modern times until 1940 when the musicologist and recorder player Walter Bergman rediscovered them and published three of them for Schott.